In recent years GraphQL has really taken off as a pattern/library/type system. It offers much which REST does not and its standardisation and flexibily has really helped in its adoption. When I began looking for a detailed explanation of how graphql works internally I struggled to find anything which was not too high-level. I wanted to see how the schema, query, types and resolvers all worked together mechanically.

Its not possible to focus on all parts in detail in this article so I have focused on the execution part of the query lifecycle.

This is part of my "under-the-hood of" series:

- Web bundlers (e.g. Webpack)

- Type systems (e.g. TypeScript)

- Test runners (e.g. Mocha)

- Source maps

- React hooks

- Apollo

- Auto formatters (e.g. Prettier)

A video for this talk can be found here. Part of my "under-the-hood of" series here.

The article today will be broken down into 2 parts:

1: Overview

First we need to ask what is graphql? There are a couple of answers

It is:

- A type system - type definitions define how data should look. They are written to show what is included and highlight the relationships (how things relate). This system definition language can be transformed into AST.

- A formal language for querying data - what to fetch from where.

- Rules for validating or executing a query against the Schema.

Point (3) above references the official Specification which defines the rules for types, validation and executing the schema. It can be found at:

There is also a documentation-friendly website graphql.org/learn

All languages follow the spec, and the JS graphql library frequently references part of it. We will be looking at that library as part of this section.

Building the schema

Building the schema is important part for a graphql application, as mentioned above it defines all types and their relationships. There are 2 steps to this

1. Parses "schema notation" (usually found in a schema.graphql file) into AST

The parser will throw errors if it is not a GraphQL schema. See snippet from types/schema.js (below)

export function isSchema(schema) {

return instanceOf(schema, GraphQLSchema)

}2. Transform AST into objects and instances

We need a schema which is a type instance of GraphQLSchema (see above snippet). We then need objects inside the schema which match types, for example a scalar or an object.

Example of a scalar (below snippet)

const OddType = new GraphQLScalarType({

name: "Odd",

serialize(value) {

if (value % 2 === 1) {

return value

}

},

})The native scalar types defined for GraphQL are ID, Int, Float, String and Boolean. You can define your own inside your type system.

Summarise

Essentially for building the schema we turn this graphql schema notation:

type Book {

id: ID!

title: String

authors: [Author]

}Into this Javascript

const Book = new GraphQLObjectType({

name: 'Book',

fields: () => ({

id: { type: new GraphQLNonNull(GraphQLID) },

title: { type: new GraphQLString },

author: { type: new GraphQLList(Author) },

})

}Almost all of the GraphQL types that you define will be object types. Object types have a name, but most importantly describe their fields.

A GraphQLSchema looks like the below in raw POJO form:

GraphQLSchema {

astNode: {

kind: 'SchemaDefinition',

...

},

extensionASTNodes: [],

_queryType: Query,

...

_typeMap: {

Query: Query,

ID: ID,

User: User,

String: String,

...

},

...

}It holds AST information too but the root Query and types are found under the _typeMap property.

Adding resolvers

Resolvers cannot be included in the GraphQL schema language, so they must be added separately.

They are added to the _typeMap property, under _typeMap.<Type>._fields.<field>

So after adding the resolvers, a schema object might look like below:

e.g.

_typeMap: {

Query: { _fields: { users: { resolve: [function] } } },

User: { _fields: { address: { resolve: [function] } } }

}From the HTTP request side the community has largely standardized on a HTTP POST method. But what happens when the server receives a query?

Query lifecycle

The GraphQL spec outlines what is known as the "request lifecycle". This details what happens when a request reaches the server to produce the result.

There are 3 steps that occur once the lifecycle is triggered.

1. Parse Query

Here the server turns the query into AST. This includes:

-

Lexical Analysis

- GraphQL's Lexer identifies the pieces (words/tokens) of the GraphQL query and assigns meaning to each

-

Syntactic Analysis

- GraphQL's parser than checks whether the pieces conforms to the language syntax (grammar rules)

If both these pass the server can move on.

In graphql-js this is all found under the parser.js file and function.

This query:

query homepage { posts { title author } }

Becomes the AST

{

"kind": "Document",

"definitions": [

{

"kind": "OperationDefinition",

"operation": "query",

"name": {

"kind": "Name",

"value": "homepage"

},

"selectionSet": {

"kind": "SelectionSet",

"selections": [

{

"kind": "Field",

"name": {

"kind": "Name",

"value": "posts"

},

"selectionSet": {

"kind": "SelectionSet",

"selections": [

{

"kind": "Field",

"name": {

"kind": "Name",

"value": "title"

}

},

{

"kind": "Field",

"name": {

"kind": "Name",

"value": "author"

}

}

]

}

}

]

}

}

]

}You can see this for yourself on astexplorer under GraphQL.

2. Validate Query

This step ensures the request is executable against the provided Schema. Found under the validate.js in the graphql-js library.

While it is usally run just before execute, it can be useful to run in isolation. For example by a client before sending the query to the server. The benefit is that the validator could flag an invalid query before it is sent to the server, saving a HTTP request.

It works by checking each field in the query AST document against its corresponding type definition in the schema object. It will compare argument type compatibility as well as coercion checks.

3. Execute Query

This step is by far the most intensive and the step I often found the most confusing in its mechanism. We will be digging deeper into this step in part 2, so lets look at the process involved from a high-level.

- Identify the operations i.e. a query or mutation? (several queries can be made at once)

- Then resolve each operation.

For step (2) each query/mutation is run in isolation.

Resolving each operation

For step 2 GraphQL iterates over each field in the selection-set, if it is a scalar type resolve the field (executeField) else recurse the selection-sets until it resolves to a scalar.

The way this works is that the engine calls all fields on the root level at once and waits for all to return (this includes any promises). Then after reading the return type it cascades down the tree calling all sub-field resolvers with data from the parent resolver. Then it repeats this cascade on those field return types. So simply speaking it calls the top-level Query initially and then the root resolver for each type.

The mechanism caled "scalar coercion" comes into play here. Any values returned by the resolver are converted (based on the return type) in order to uphold the API contract. For example a resolver returning string "123" with a number type attached to it will return Number("123") (i.e a number).

This is found under the execute.js file and function inside graphql-js.

Lastly the result is returned.

Introspection system

Its worth mentioning the introspection system. This is a mechanism used by the GraphQL API schema to allow clients to learn what types and operations are supported and in what format.

The clients can query the __schema field in the GraphQL API, which is always available on the root type of a Query.

Any interactive GraphQL UIs rely on sending an IntrospectionQuery request to the server, which builds documentation and auto-completion with it.

Libraries

As part of my research I covered many different libraries, so I thought it was worth giving a quick overview of the main ones in the JS ecosystem.

graphql-js

The reference implementation of the GraphQL spec, but also full of useful tools for building GraphQL servers, clients and tooling. It's a GitHub organisation with many mono-repositories.

It performs the entire Query Lifecycle (including parsing schema notation).

Schema

Requires library specific GraphQLSchema instance. In order to be an executable schema it requires resolver functions.

Example functions

- Take output of introspection query and builds the schema out of it

buildASTSchema

- Once you have parsed the schema into AST this then transforms into a

GraphQLSchematype

graphql-tools

It's an abstraction on top of graphql-js. Houses lots of functionality including generating a fully spec-supported schema and stitching multiple schemas together.

Example functions

makeExecutableSchema

-

Takes arguments

typeDefs- "GraphQL schema language string" or arrayresolvers- is an object or array of objects

- Returns a

graphql-jsGraphQLSchemainstance

loadSchemaSync

- Point this to the source to load your schema from and it returns a

GraphQLSchema.

- Takes a

GraphQLSchemaandresolversthen returns an updatedGraphQLSchema.

apollo-server

It's also an abstraction on graphql-js. Uses the graphql-tools library for building GraphQL servers.

Introspection is disabled on production by default but on non-production it uses introspection to expose a /graphql playground.

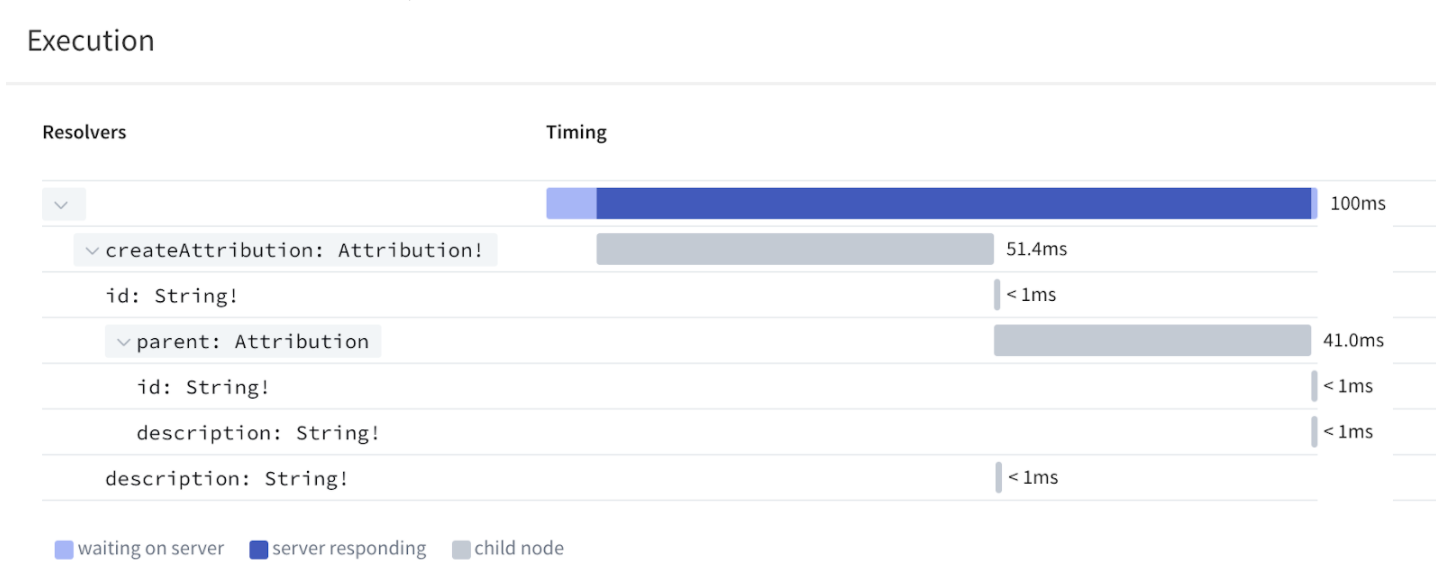

Apollo Studio

Not really a library but I thought worth a mention.

Plugs into apollo-server and provides stats and information of your GraphQL server in realtime. Such as:

- Monitoring operations

- Tracking errors

- Profiling resolvers (see example on below screen)

2: Building our own GraphQL executor

Here we will build our own GraphQL execute function that a parsed query and our schema can run against. It will ignore any validation. We will use GraphQL instance types to create a schema, ignoring the schema parsing step.

We saw earlier in the query lifecycle section that the graphql-js library contains the necessary functions and they can be imported individually for usage. e.g. parser(), validate() and execute(). In addition to those functions it also exports type instances which can be used to build up a graphql schema. While we WILL NOT be using any of the functions they provide, we WILL BE using the type intances they provide to build a valid schema.

We will be using 3 different scenarios to examine the mechanism in place.

Before we go any further here are some of the common terms mentioned.

Terms

-

Definitions

- Name for top-level statements in the document

- Most GraphQL types you define will be object types and they have name and describe fields

-

Operations

- The type of request i.e query/mutation

-

Selections

- They are definitions that appear at a single level of a query

- For example field references e.g

a, fragment spreads e.g...cand inline fragment spreads...on Type { a } - See in the spec

-

Execution Context

- Data that must be available at all points during the queries execution.

- Includes the Schema of the type system currently executing and fragments defined in the query document

- It is passed into the resolver as

context - Commonly used to represent an authenticated user or request-specific cache

-

Resolvers

- Functions to populate data for a field in your Schema

- Can return a value, a promise or an array of promises

This part is split into 2 steps.

Step 1 - Query and schema

Step 1 is to gather our query AST and schema instances using graphql-js, so they are ready for processing

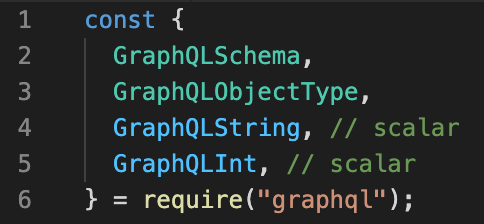

These are the types which we will be importing from the graphql-js library. 2 scalars, 1 object and the schema type.

The query will look like below, it is close to how a normal graphql query would run, except usually there is an extra parse(query) step before execution.

// "document" = is our query in (hardcoded) AST form

const schema = new GraphQLSchema({ …<schema objects> })

// GraphQLSchema contains class instances of root-level query, fields, types, resolvers

ourExecute({ schema, document });

// execute query AST with schemaNormally this would be:

// schema = built from "schema.graphql" and "graphql-tool" loadSchemaSync/makeExecutableSchema/addResolversToSchema

const document = parse(query)

execute({ schema, document })We will be looking at 3 scenarios. Each scenario below will contain 2 images.

- The query AST - This is the query put into AST form

- The schema - This is how the schema looks (see comment for pre-schema parsing form)

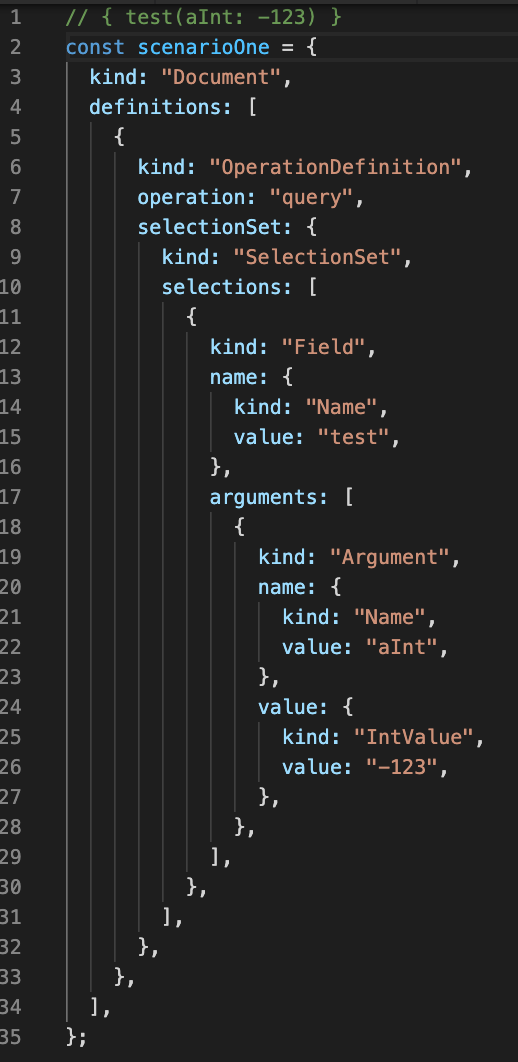

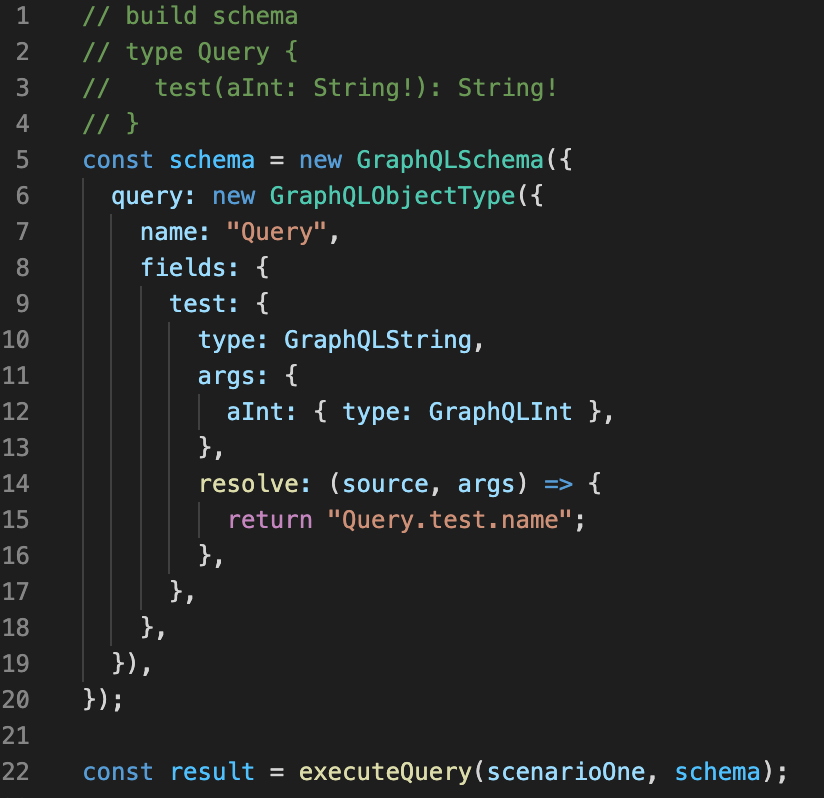

Scenario 1

A root query with resolver args.

Query: { test(aInt: -123) }

Query AST

Schema

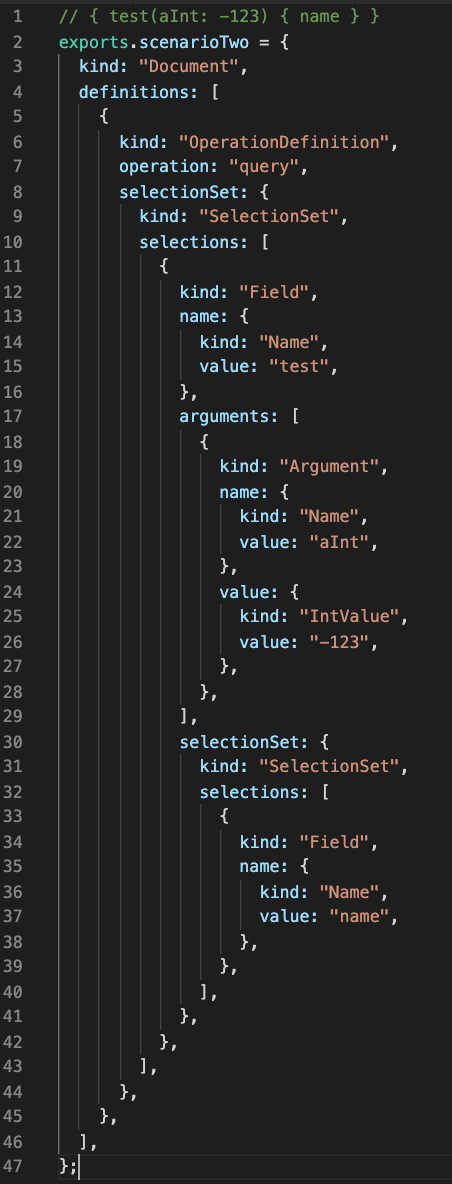

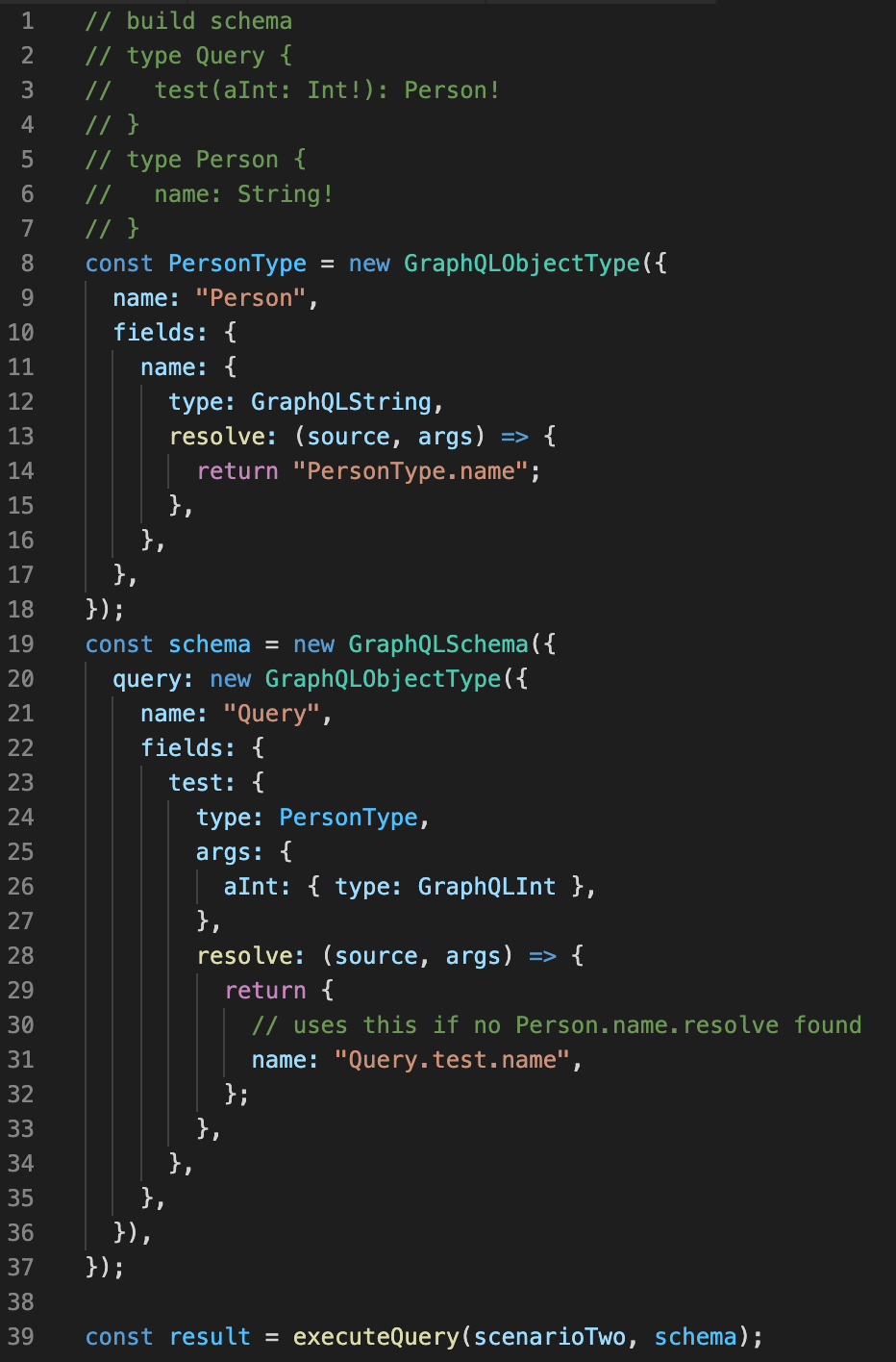

Scenario 2

A root query with inner object and resolver args.

Query: { test(aInt: -123) { name } }

Query AST

Schema

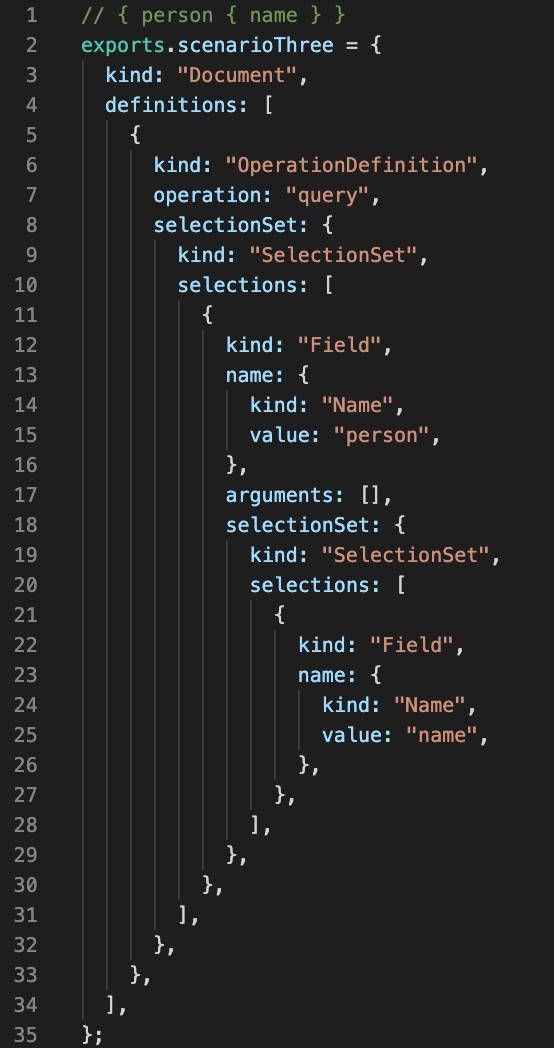

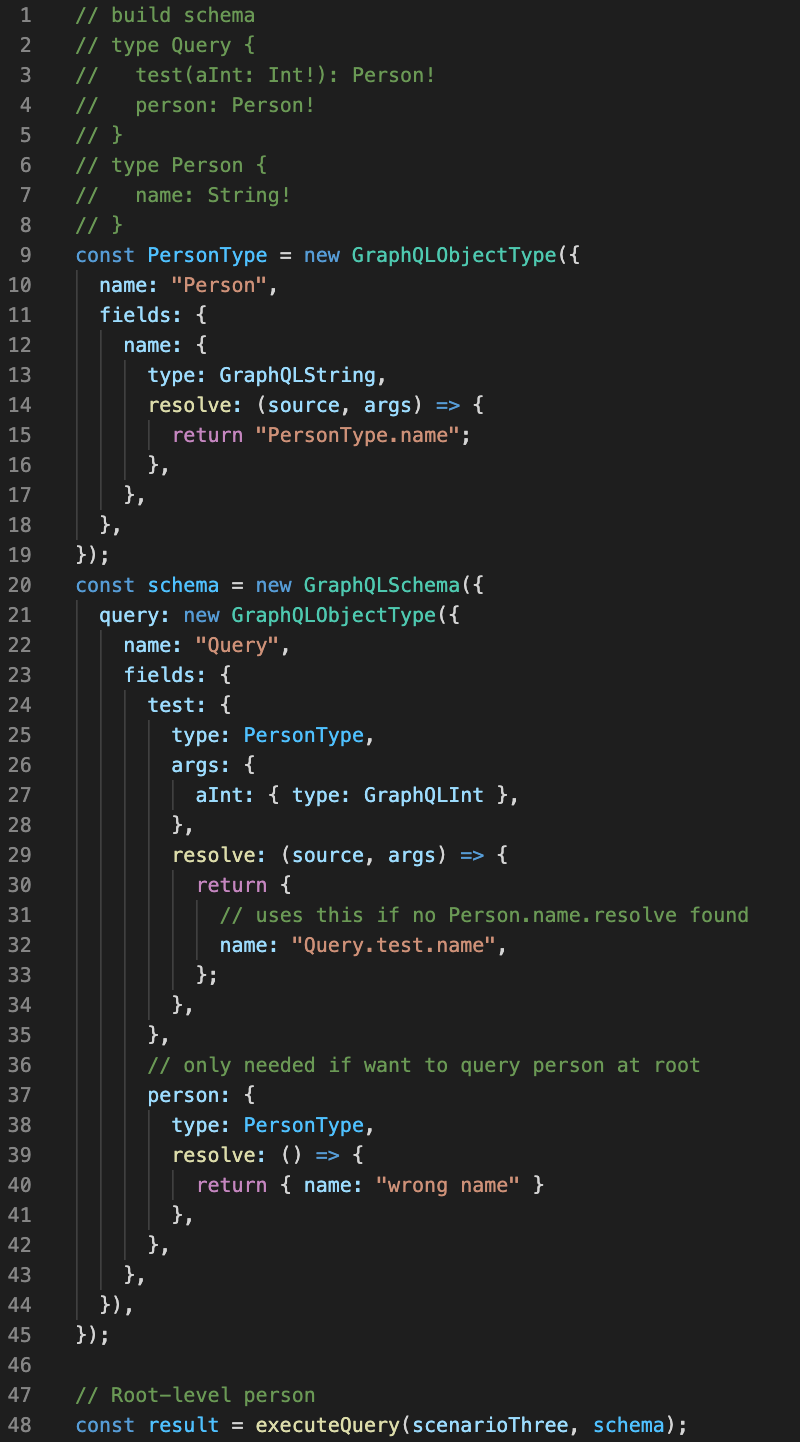

Scenario 3

A different root type with inner object.

Query: { person { name } }

Query AST

Schema

Step 2 - Execute

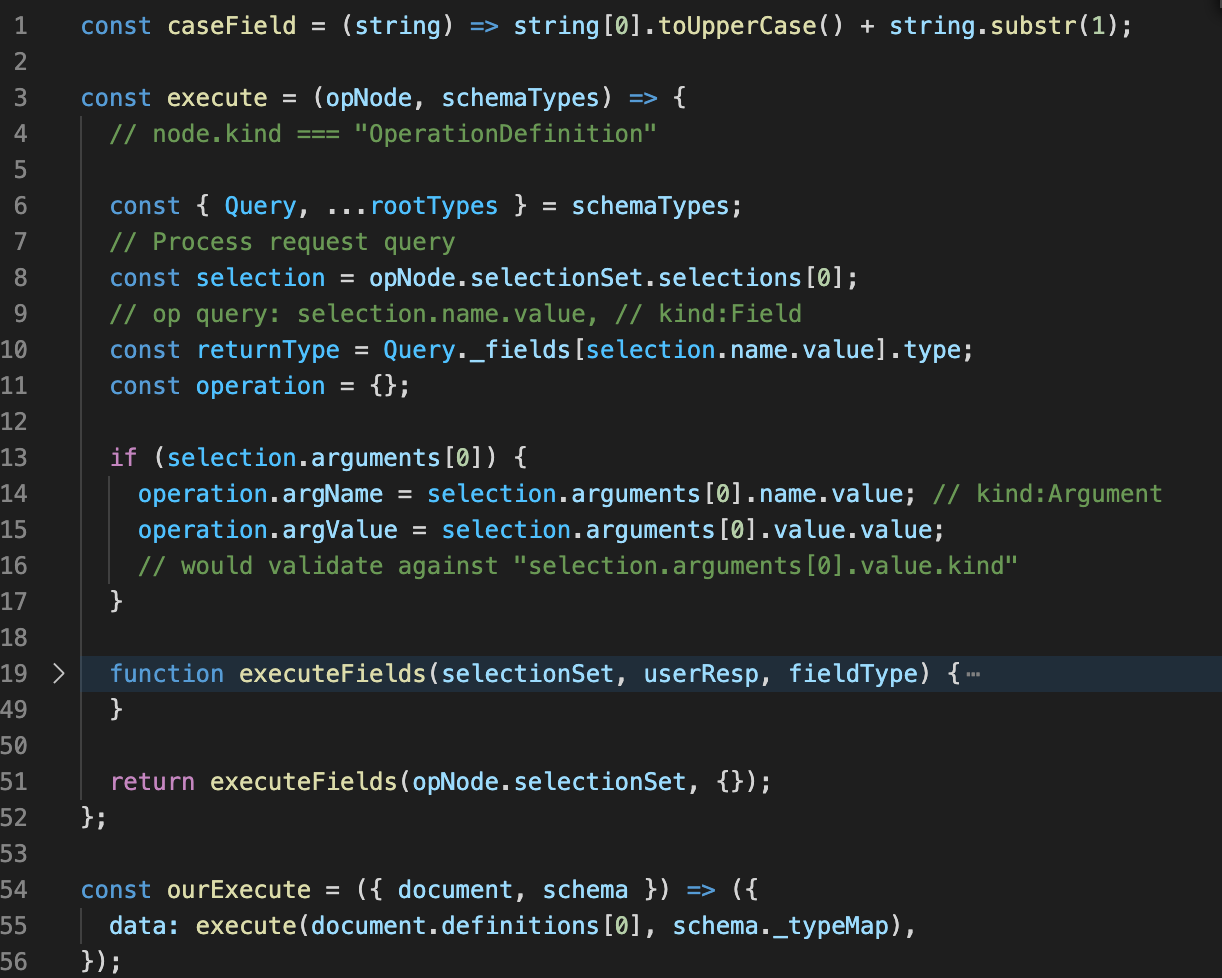

Now that we have the setup complete for 3 scenarios we will look to build our actual execute function. The code is below and will be explained.

Starts on line 54. Here we call execute with our first definition as well as the types map. So we are limiting our POC to the first operation which we know is the query. In reality it would iterate over the definitions.

Inside execute (line 3) we grab the Query and rootTypes (line 6), then process the first selection in the selection set (line 8). Again hardcoded for this POC. We then grab the returnType (line 10) this would be used for validation against the query result, I have omitted that here. Line 11 creates an empty operations object to store any operation arguments on for later.

On line 13 we check for arguments and grab the argument name and value. We could also grab the type (line 16) which would be used for validation.

We define executeField on line 19, we will go through that next. Lastly we call executeFields with our current selection-set and an empty object. This will make up our response to return.

Now on to executeFields. It takes a selection-set, response object and field type as arguments. This is so it can call the query tree recursively and build the response data as we go along.

Line 20 we iterate over all selection-set selections (so this part works with multiple selections). We grap the field (line 21) and check for it on the root query level (line 24). For "Scenario 1" the field is user. So it checks Query._fields[user].resolve, which does exist for "Scenario 1".

If it exists (i.e. "Scenario 1") we call the resolver with the argument name and value, and then place the data returned from the resolver onto that field name (e.g. user) on the response (line 28).

Line 32 we then check if the return types field exists on the Schemas rootTypes object. If so we execute it with the parents resolver data and then write that to the field on the response (line 36). For "Scenario 1" the returnType is a String, as a scalar this does not have _fields so this would not trigger. For "Scenario 2" the returnType is a Person which has _fields, one of which is name but right now the field is test so would not trigger until recursed below.

Line 40 and 41 we check if this selection has got selection-sets itself and if so execute those. We hand the selection-set, the current response data for this field, and the current field name. So we are recursively calling executeFields with the deeper selection sets and building up a single response to return. "Scenario 2" will call the root query resolver first, then call executeFields again with the inner name field, where the fields resolver will be found and called with the existing resolver data.

Lastly we return the built response data on line 48, see userResp.

Its worth noting we have omitted any scalar checks, with the real graphql-js.execute the field type is checked as part of the validation to make sure that non-scalars should have sub selections. However line 32 (rootTypes?.[returnType]?._fields?.[field]?.resolve) is a kind of scalar check (scalars don't have _fields).

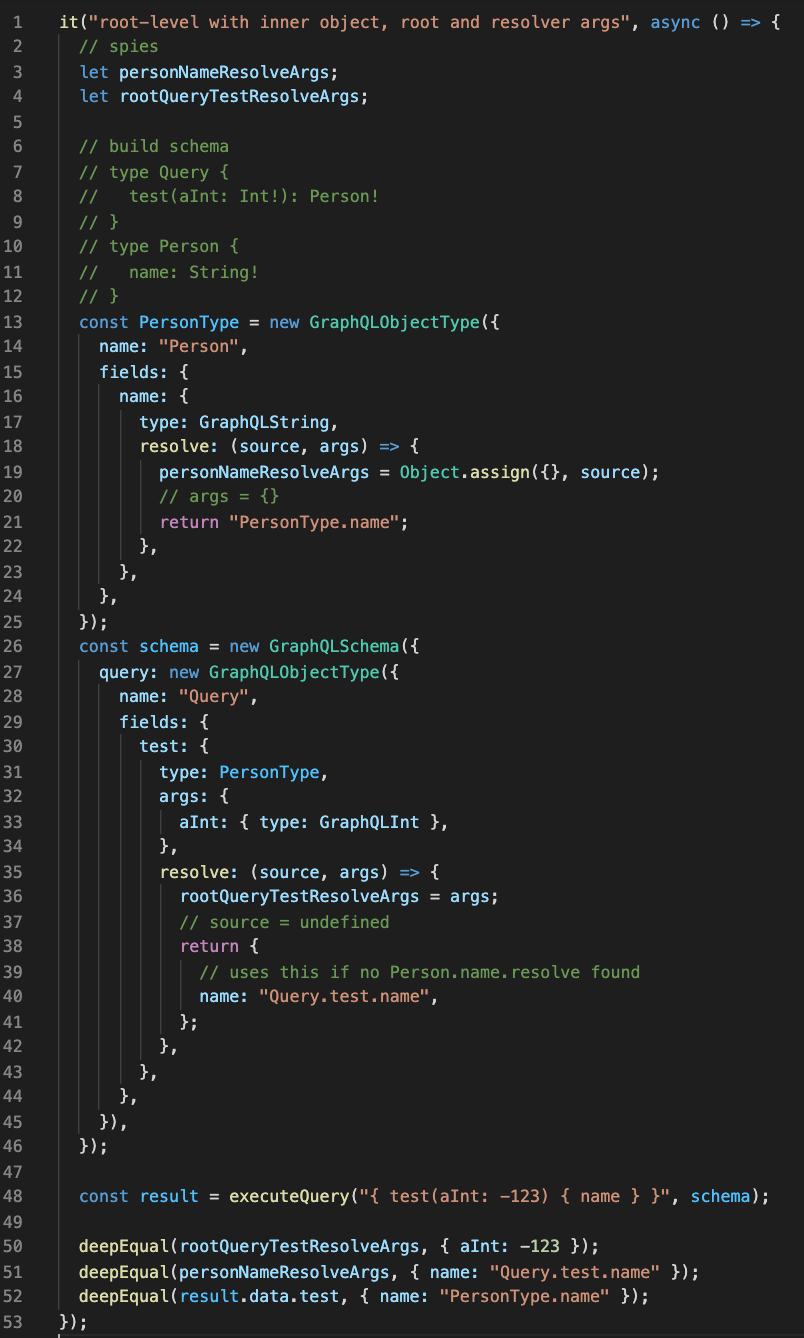

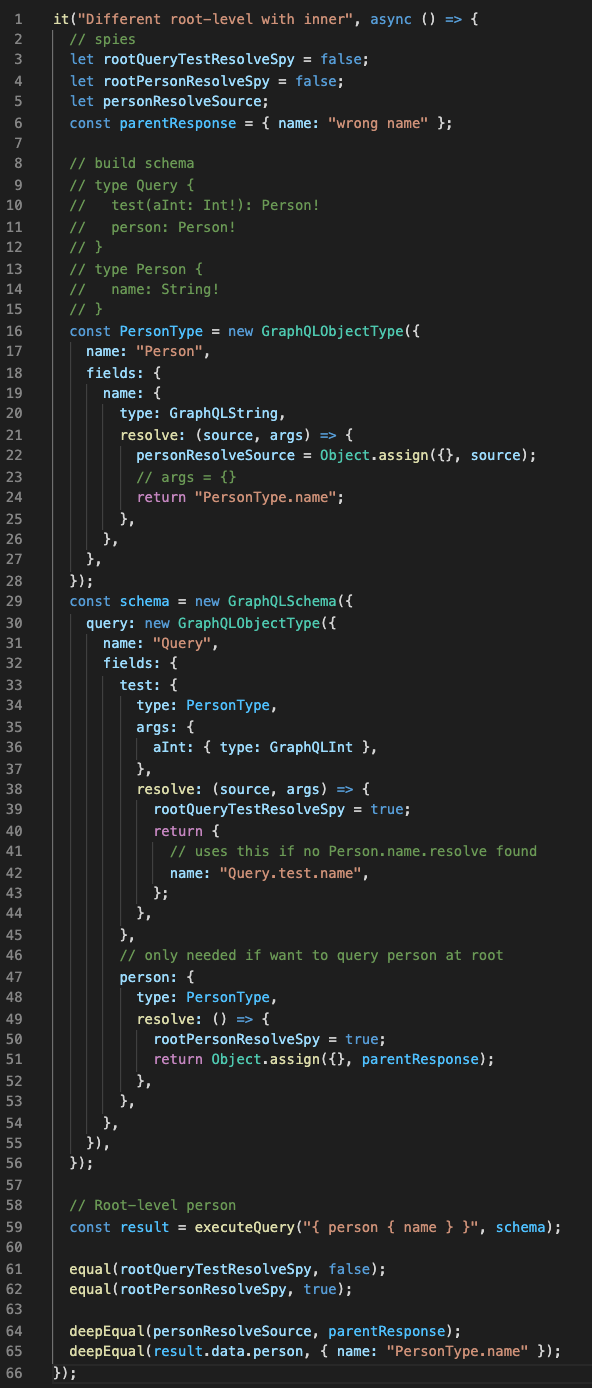

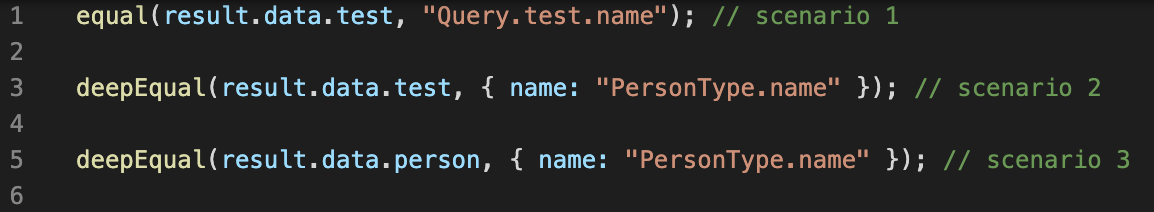

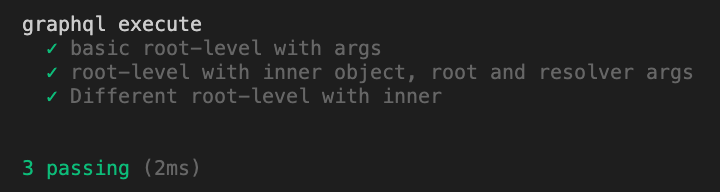

Checking results

In order to check this would work I wrote some unit tests found here. It includes some pure assertions as well as spies and I initially ran them against graphql-js.execute() to ensure they were written correctly. I then swapped to using my executor. The schema objects are those shown earlier, but this is all of it together.

Scenario 1 looks like this

Scenario 2 looks like this

Scenario 3 looks like this

A summary of the data assertions is here:

Here is the results of the test runner:

It works !!! Good job 👍💪

I encourage anyone that is interested to check out the code and play with the mechanism yourself.

What have we missed?

As mentioned there are many additional parts to the real graphql executor which we have omitted from our library. Some of those are:

- Scalar type checks and scalar coercion

- Processing multiple queries at once

- Building response data not via pass-by-ref

- Handling more complex scenarios

- Validation of query (including errors)

- Execution context - would be passed into the resolver.

Thanks so much for reading (or watching), I learnt a huge amount about GraphQL from this research and I hope it was useful for you. You can find the repository for all this code here.

Thanks, Craig 😃